Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg began her career as a litigator after graduating at the top of her class from Columbia Law School in 1959. She was one of 12 women to pass through the program that year.

In the decades to follow, she would deliver key arguments on landmark gender discrimination cases of the 20th century. Her death earlier this Friday evening—less than seven weeks before Election Day—opens up a new political battle over the future of the Supreme Court, and over legislative decisions for decades to come.

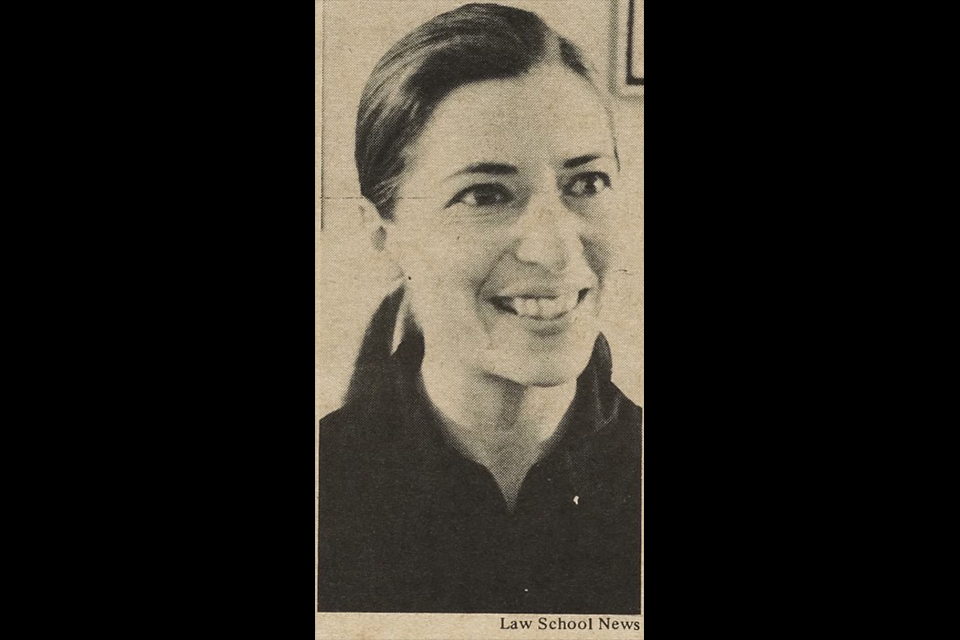

Even before she took her place on the bench, Ginsburg changed the landscape for women in law at Columbia. Read our 1972 article from the Spectator Archives, when Ginsburg became the first woman to be appointed as full professor by the Law School.

The first woman ever appointed full professor at the Columbia Law School yesterday credited the current feminist movement with “creating the intellectual climate” that made her appointment possible and voiced her intention of working with campus women’s groups when she arrives at Columbia next fall.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg, at an interview held in her East Side apartment last night, expressed the belief that her appointment “reflects a serious effort on the part of the Columbia Law School to hire more women faculty members. I know that I am not just a token. I expect that I will be the first of many women professors the law. school will have.”

Professor Ginsburg, who has been a professor of law at Rutgers, the state university of New Jersey, since 1969, asserted that she felt that her selection by Columbia is “a sign of an awakening of the law school and perhaps of Columbia as a whole to the necessity of ending sexual discrimination.”

“The process of change is beginning,” she continued, “and I, personally, have no doubts that it will go further. We are now at a point in history that has never been reached before as far as the opportunities for women are concerned, and we cannot go back to the situation that existed before.”

Professor Ginsburg, who has been closely involved in the problems of sexual discrimination from the point of view of both lawyer and victim, disclosed that next fall, in addition to teaching courses on the more traditional subjects of procedures and conflicts she will give a new course on sexual discrimination.

“Sexual discrimination is and will continue to be my principal interest,” she asserted. “It is an area new to the law school, an area that has been neglected far too long.” She added that in addition to the course she will be teaching, she hoped that material on the legal aspects of sexual discrimination would be integrated into the rest of the law school curriculum.

Professor Ginsburg, who had been sought by law schools throughout the country, noted that one of the reasons she accepted a position at Columbia was that she had already been appointed supervisor of an American Civil Liberties Union project on sexual discrimination in New York. She added that she hoped to co-ordinate the second semester of her course with actual civil liberties cases that will occur in her work with the civil liberties union.

Professor Ginsburg said that she has long been affiliated with the ACLU and has been involved in many cases dealing with sexual discrimination. She wrote the legal brief in the case of Reed v. Reed, which resulted in the first Supreme Court verdict, handed down last November, which clearly found sexual discrimination unconstitutional.

She is currently deeply involved in the litigation of a female college student who was prevented from joining the all-male tennis team at her school.

“In this case,” Professor Ginsburg commented, “the woman was told she could play against women but not against men. Suppose a black student had been told he could play only against blacks. It is clear that this form of racial discrimination would not be tolerated where sexual discrimination now is.”

Professor Ginsburg, who is now writing a textbook on sexual discrimination, is no stranger to this prejudice herself. She graduated from Columbia Law School in 1959 tied for first place in her class, yet could not land a job with any law firm. “I think that if I had been a man,” she observed, “I would have had at least a dozen offers.”

She finally obtained a position clerking for a Federal district judge, and after the first two years, noticed “a big difference” in the way she was treated. “I suppose I showed that a woman could be punctual and have a good attendance record,” she wryly noted.

In discussing the reception she received from the law school faculty, Professor Ginsburg noted that “while it’s an all-male faculty with the usual suspicions about women, I was made to feel very welcome by them.”

“I don’t think there is any question in the minds of the Columbia faculty that there are many women wno are quite capable in the law,” she stated.

Discussing the thirty maids recently fired by the university, Professor Ginsburg said that she was not too familiar with the particulars of the dismissals, although she had previously observed similar cases.

“It is common in many institutions for there to be two lines of seniority, one for men and one for women, with the men paid more than the women. Of course, janitors will usually be given extra duties that the maids do not have, but these are usually thrown in to justify the extra pay,” she said.

From the Spectator Archives, this article was originally published February 16, 1972.

"first" - Google News

September 19, 2020 at 09:15AM

https://ift.tt/2REXVej

FROM THE ARCHIVES: Law school names first Woman Professor - CU Columbia Spectator

"first" - Google News

https://ift.tt/2QqCv4E

https://ift.tt/3bWWEYd

Bagikan Berita Ini

0 Response to "FROM THE ARCHIVES: Law school names first Woman Professor - CU Columbia Spectator"

Post a Comment